Women in Politics Guest Blog: Margaret Nygard

Posted on October 12, 2020

This guest blog was contributed by Jim Wise, Durham Historian and former MoDH board member.

It may have been a Durham Morning Herald headline, “City Proposes Dam on Eno,” or words to that effect. It may have been a chemical spill that produced an odiferous fish kill near her riverside home. It may have been something else, but whatever, it moved Margaret Nygard to take on City Hall and win – and today Durham has a city park, a state park and a clean-running Eno River to show for it.

Eco-consciousness was not particularly high on Durham’s priority list in the mid-1960s, but water was – the kind you drink, bathe in and wash with. With a growing population and a Research Triangle Park just hitting its stride, the municipal water system was closing in on the capacity of 40-year-old Lake Michie. Water authorities were pressing the city council to plan a reservoir on the long-untapped Eno.

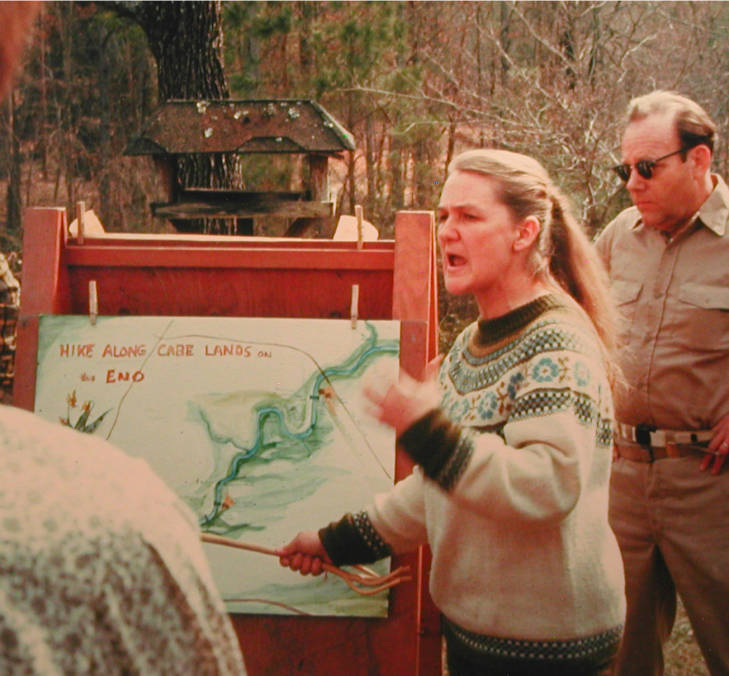

Nygard and her husband, Holger, liked and appreciated the river and the forest along its banks as they were. They began an opposition movement along with a few like-minded neighbors. Their tactics were public nature hikes, float trips, slide shows, maps and lobbying, lobbying, lobbying city officials – who at first considered the Association for the Preservation of the Eno River Valley a nagging nuisance in the midst of the era’s other concerns.

Still, the charismatic Nygard and her growing cohort of fellow travelers kept on and by the end of 1968 – just two years after the Association’s formation on Oct. 14, 1966 – regional planners had moved an Eno reservoir well down on their agendas. (That second reservoir would be built in the 1980s on the Little River.) Still, with a future Lake Eno in view, the city had bought up a sizable tract along the river, and Nygard’s group began a push to have that turned into a nature and history park instead of an office- and condo-rimmed “regional scenic attraction.”

About this same time, the fledging North Carolina Nature Conservancy had taken up the cause and prompted the indefatigable Nygard and Associates to press the state for a preservation park all along the Eno. As a result, the Eno River State Park came into being in 1973. As another result, City Hall had been brought a long way around to the environmentalists’ way of thinking.

In 1963, a city-sponsored newspaper supplement carried a photo of a bulldozer at work in a flattened landscape, proudly captioned “This is a familiar scene in Durham.” Thirteen years later, Durham offered its homegrown version of a national Bicentennial observance: a North Carolina Folklife Festival that opened the city’s brand-new West Point on the Eno.

Times do change, but it takes a little prompting.

Nygard, an India-born Brit who was a teacher and social worker in other lives, died in 1995 as she was getting ready for the Eno Association’s annual meeting. An activist once laughed at by Durham authorities was recognized as a latter-day prophet.

“People do realize now that land is not to be taken for granted,” said Hildegard Ryals, who delivered a eulogy at Margaret Nygard’s funeral. “The natural environment for all of us, all of the living creatures – people don’t laugh.”

But there’s more to the story –.