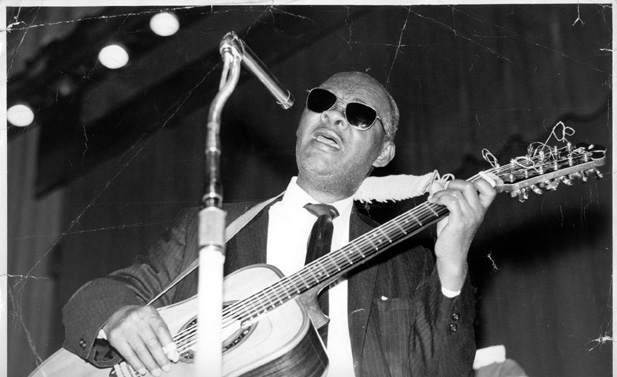

Meet the Faces of Durham: Reverend Gary Davis

Posted on February 9, 2021

Faces of Durham features a selection of familiar and lesser-known faces from the Bull City’s past and present. The exhibit highlights a broad range of contributions including industry and commerce, medicine, and human relations while mapping Durham’s development from a railway stop to a booming tobacco town, and to today’s revitalized hub of arts and innovation. Check out our blog as we introduce some of the faces from the exhibit.

Reverend Gary Davis, also known as Blind Gary Davis, was born in Laurens, South Carolina, to a rural black family in 1896. During his infancy he became blind and was subsequently raised by his grandmother due to his mother’s rejection and his father’s constant legal difficulties. Reflecting on growing up as a blind black man in the Jim Crow South, Davis recalled: “Since I was a man that come up that didn’t see, that perhaps if I had been a man that could see like the others… I might have seen more than I cared to look upon… And many times where many people have been strung up on limbs in the low countries [i.e., the South] and lynched just by looking.”

During his formative years, Davis taught himself to play guitar, banjo, and harmonica and began playing at local folk dances for white people and at the Center Raven Baptist Church in Gray Court, South Carolina. At age 18, he received a scholarship to attend the South Carolina Institution for the Education for the Deaf and Blind at Cedar Springs, Spartanburg, where he learned to read Braille, but left after six months. During the 1910s and 1920s, Davis played in a local string band in Greenville, South Carolina, which was then a center of the Piedmont blues style. In the mid-1920s, he married and traveled around South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee as a street musician. Around this time Davis broke his left wrist after slipping on the snow, but this accident would in fact aid his musical style since he displayed a remarkable ability to play unusual chord patterns not possible for a normal wrist.

After settling in Durham, Davis became influential in the blues scene and displayed a particular aptitude for spiritual music since it provided him with “a floor for his despair” and a means for self-assertion. He was ordained a Baptist minister in 1933 in Washington, North Carolina, and turned his focus to gospel music. In 1935 Davis came to the attention of J.B. Long, who recruited him to record for ARC in collaboration with Blind Boy Fuller. Between July 23 and July 26, he recorded 15 sides, including ten Christian songs and two sets of blues, “I’m Throwin’ Up My Hand” and “Cross and Evil Woman Blues.” Davis became disillusioned with ARC since he was paid less than the other performers, and he refused when Long asked him to record again in 1939.

Davis later moved with his second wife, Annie Bell Wright, to New York, where he preached as a minister and taught guitar. During the 1950s and 1960s he toured Europe and became integral to the 1960s folk revival, performing at the Newport Folk Festival which marked the peak of his career. On May 5, 1972, Reverend Gary Davis suffered a heart attack and died at William Kessler Memorial Hospital in Hammonton, New Jersey. He is buried in Rockville Cemetery in Lynbrook, New York. A major influence among later folk singers, a large part of Davis’ music was published posthumously, even inspiring non-believers like Allen Evans who commented that he came to appreciate the faith of devout audiences as “an act of goodness to others, distinguished by an absence of proselytizing, moralizing or judgmental admonitions…”

This post was written by our Spring 2021 intern from UNC-Greensboro, Nils Skudra.