Local Protest in Dining Establishments

Posted on June 8, 2022Although mid-20th century cuisine across Durham consisted of many of the same southern dishes, the experiences of Black and White diners differed greatly in the Jim Crow south. While most White-owned restaurants refused to seat African Americans, Black-owned restaurants opened to provide safe and comfortable dining for local Blacks and Black travelers. Between 1936 and 1966, the Negro Motorist Green Book was a vital guide for African American travelers to identify safe places to eat and sleep.

There were some White-owned establishments that promoted integration and were instrumental in desegregation efforts. Mayor Emanuel “Mutt” Evans, Durham’s first Jewish mayor (1951-1963), ran the only integrated lunch counter in downtown Durham during the 1950s. Evans United Department Store, which had a large Black customer base, seated Black and White diners, until authorities, citing a local segregation ordinance, pressured Evans to build a wall between Black and White sections in his restaurant. Refusing to abandon his pro-integration stance, Evans found a loophole in the segregation ordinance. By raising the height of the counters to leaning height and removing the chairs, he successfully continued to serve both Blacks and Whites at the restaurant. (Pictured: Evans’ United Department Store located on West Main Street. Courtesy of the Herald-Sun)

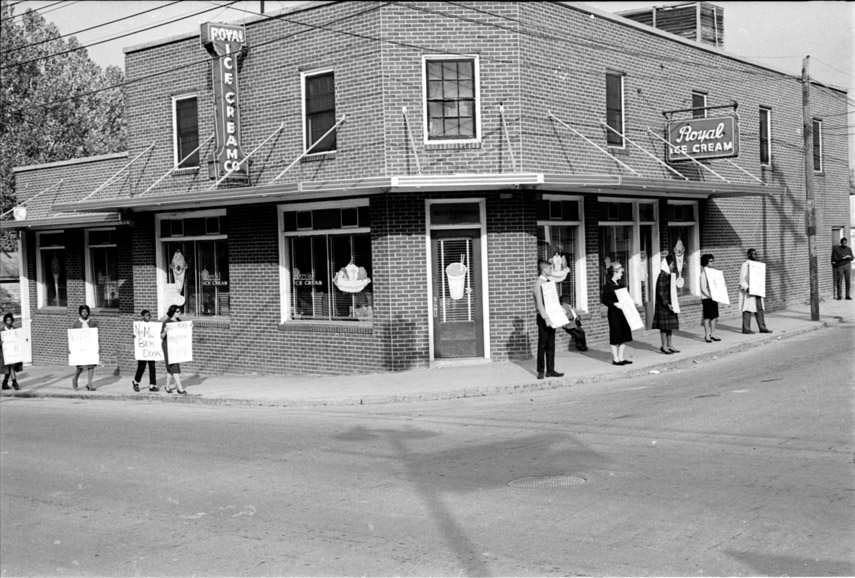

On June 23, 1957, Rev. Douglas E. Moore led six young African American men and women – Mary Elizabeth Clyburn, Claude Glenn, Jesse Gray, Vivian Jones, Virginia Williams, and Melvin Willis – in a nonviolent protest at the Royal Ice Cream Parlor. After refusing to leave the “Whites Only” section of the parlor, the group was arrested and charged with trespassing. Durham’s Royal Ice Cream Parlor sit-in was one of the earliest of its kind in the state. (Pictured: Protestors march outside the Royal Ice Cream Parlor. Courtesy of the Herald-Sun)

Three years later, on February 1, 1960, the famous Woolworth’s sit-in in Greensboro took place with a similar one following in Durham the next week. Over forty North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University) students and four from Duke University organized sit-ins at the Durham lunch counter. This prompted Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to visit Durham where he gave his “A Creative Protest” speech.

After the arrest of several students during a protest at the Howard Johnson’s Restaurant on Chapel Hill Boulevard, the protests reached a crescendo in May 1963, when over 4,000 demonstrators converged on Howard Johnson’s in the largest protest in Durham’s history, demanding the integration of all public facilities in the city.

Following a month of massive demonstrations in favor of integrating public facilities, newly elected Mayor Wensell “Wense” Grabarek formed the Durham Interim Committee on Race Relations. The committee consisted of two Black members, Asa Spaulding and John Wheeler, and nine White businessmen, including cafeteria owner Harvey Rape, and was tasked to “resolve and reconcile” racial differences. By the end of the year, the protests and boycotts as well as the committee’s efforts had forced most Durham restaurants, hotels, and other public facilities to integrate. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the remainder of Durham’s public spaces were legally desegregated.